What Immunosuppressants Do and Why They’re Lifesaving

After an organ transplant, your body sees the new organ as an invader. It doesn’t matter if it’s a kidney, heart, or liver - your immune system will try to destroy it. That’s where immunosuppressants come in. These drugs don’t cure anything. They don’t fix the organ. They just stop your body from attacking it. Without them, most transplants fail within days.

Today’s regimens are far better than what existed in the 1950s. Back then, up to 80% of kidney transplant patients rejected their new organs. Now, thanks to combination therapy, that number has dropped to under 15%. But here’s the catch: the drugs that save your new organ also put you at risk for serious problems. Infection. Cancer. Organ damage. And if you miss a dose, you could lose everything you’ve been through.

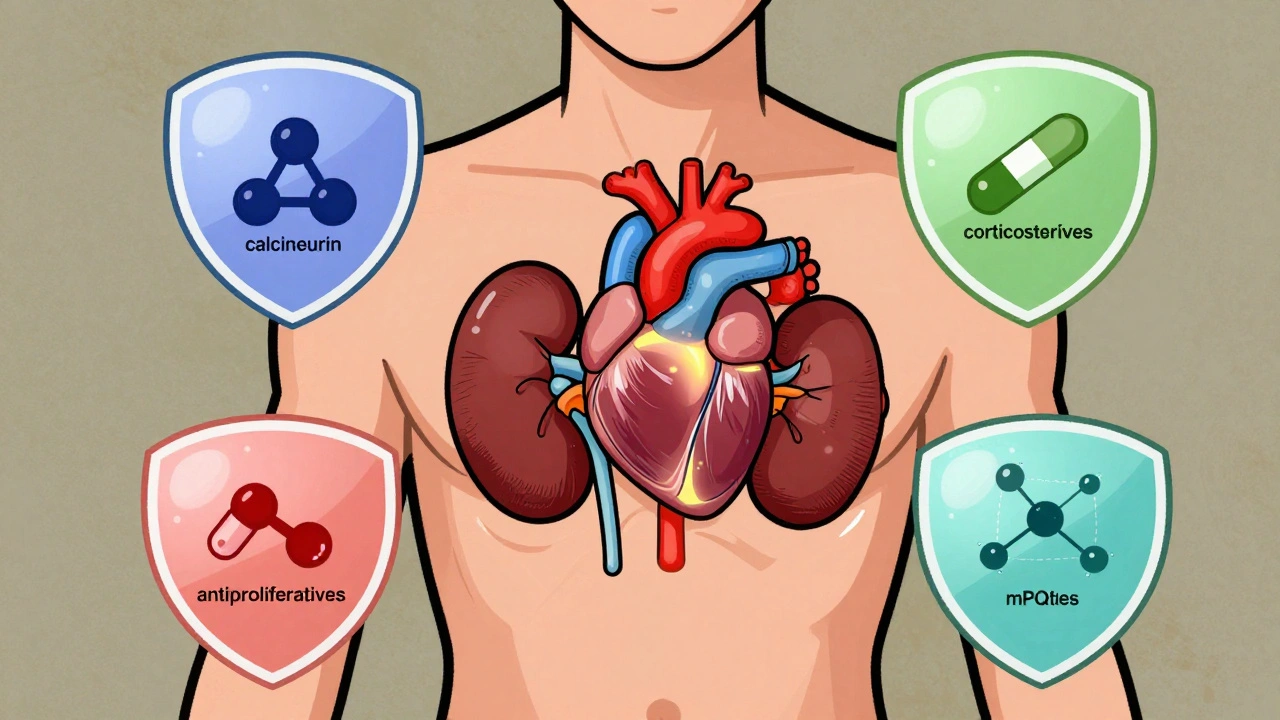

The Four Main Classes of Immunosuppressants and Their Risks

There are four major types of anti-rejection drugs, each with different ways of working and different side effects. Doctors usually mix them to get the best balance - enough suppression to prevent rejection, but not so much that your body can’t fight off a cold.

- Calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs) - Cyclosporine and tacrolimus are the most common. They block T-cells, the immune system’s main attack force. But they’re hard on the kidneys. About 30-50% of long-term users develop chronic kidney damage from them. They also raise blood pressure, cause tremors, and increase the risk of skin cancer by 2 to 4 times.

- Corticosteroids - Prednisone is the classic. It shuts down multiple immune pathways at once. But it’s a double-edged sword. Long-term use leads to diabetes in 10-40% of patients, bone loss in 30-50%, weight gain, cataracts, and mood swings. Many transplant centers now try to wean patients off steroids within a year if possible.

- Antiproliferative agents - Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) and azathioprine stop immune cells from multiplying. MMF is more commonly used today. It causes nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea in up to half of patients. About 1 in 5 people develop low white blood cell counts, which makes infections more likely.

- mTOR inhibitors - Sirolimus and everolimus work differently. They’re less damaging to kidneys than CNIs, which makes them attractive for patients with existing kidney problems. But they come with their own dangers: delayed wound healing in 20-30% of cases, severe lung inflammation (pneumonitis) in up to 5%, and a black box warning for kidney thrombosis in the first month after transplant.

There’s no one-size-fits-all. A heart transplant patient might need stronger suppression than someone with a liver. And a young person might tolerate more side effects than an older one. That’s why your doctor tailors your regimen - and why you can’t just copy someone else’s pill schedule.

Why Missing a Dose Can Be Deadly

Nonadherence is the silent killer in transplant medicine. A study of 161 kidney transplant patients found that more than half - 55% - weren’t taking their meds as prescribed. Some skipped doses. Others delayed them. A few stopped entirely when they felt fine.

Here’s what happens when you skip:

- Acute rejection can hit within weeks - swelling, fever, pain, and sudden loss of organ function.

- Chronic rejection creeps in over months or years. It’s harder to detect and harder to reverse.

- Heart transplant patients who miss doses are 3.5 times more likely to develop transplant coronary artery disease.

- For lung transplant recipients, nonadherence increases the chance of rejection by up to 72% in some studies.

The reasons? Complex schedules. High costs. Forgetfulness. Feeling healthy and thinking you don’t need the pills anymore. The truth is, you’ll never feel ‘cured.’ Your immune system never forgets the transplant. That’s why your meds aren’t optional - they’re your lifeline.

How to Stay on Track With Your Medication

Sticking to a daily pill routine for life is hard. But it’s possible - if you build systems around it.

- Use a pill organizer - One with compartments for morning, noon, night, and weekend doses. Fill it weekly.

- Set phone alarms - Three alarms, 15 minutes apart. Don’t rely on one.

- Use medication apps - Apps like Medisafe or MyTherapy send reminders, track refills, and even alert your doctor if you miss doses.

- Simplify your regimen - Ask your doctor if you can switch to once-daily tacrolimus instead of twice-daily. Many patients see a 15-25% improvement in adherence with simpler schedules.

- Keep backup pills - Always have at least a 3-day supply on hand. Traveling? Pack extra in your carry-on.

And don’t be ashamed to ask for help. Many transplant centers have pharmacists and social workers who specialize in adherence. They can help with cost issues, side effect management, and even connect you with patient support groups.

Protecting Yourself From Infections and Cancer

With your immune system turned down, everyday germs become threats. That’s why you’ll get antibiotics and antivirals for the first 3-6 months after transplant.

Common prophylactic drugs include:

- Valganciclovir - Prevents cytomegalovirus (CMV), which affects 30-70% of seronegative recipients with seropositive donors if left untreated.

- Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole - Fights Pneumocystis pneumonia and other bacterial infections.

- Fungizone or fluconazole - Stops fungal infections like thrush or candidiasis.

Outside of meds, you need habits:

- Wash your hands often - Use soap and water for at least 20 seconds.

- Avoid crowds during flu season.

- Wear a mask in hospitals or crowded indoor spaces.

- Don’t clean cat litter boxes or handle soil without gloves - toxoplasmosis is a real risk.

- Get all recommended vaccines - except live ones like MMR or yellow fever.

And cancer screening becomes critical. Skin checks every 6 months. Colonoscopies starting earlier than the general population. Regular Pap smears and prostate exams. Your doctor will set a schedule based on your drug regimen and risk level.

When and How Medications Change Over Time

Your drug plan isn’t set in stone. It evolves.

In the first week after transplant, you’ll likely be on 3-4 drugs: a biologic (like basiliximab) for induction, plus a CNI, an antiproliferative, and steroids. This is high-intensity suppression.

By month 3, your doctor will start reducing the steroids - often stopping them entirely by month 6-12. That’s because the long-term damage outweighs the benefit for most people.

After one year, you’re usually on 2-3 drugs. Maybe tacrolimus and MMF. Or everolimus instead of a CNI if your kidney function is declining.

Some centers now use biomarker-guided therapy. Instead of guessing your rejection risk, they test your blood for specific immune signals. If your risk is low, they reduce your CNI dose by 30-50%. Studies show this doesn’t increase rejection - and it cuts kidney damage.

And if your transplant fails? You stop the drugs. Not because you’re cured - but because there’s no organ left to protect. Stopping suddenly won’t harm you, but it will cause symptoms: reduced urine output (kidney), abdominal pain (liver), shortness of breath (lung), or heart fatigue (heart). That’s your body’s way of saying: the organ’s gone.

What You Need to Know About Lifelong Monitoring

You’ll never be done with doctor visits. Even if you feel great, you need regular blood tests to check drug levels, kidney function, liver enzymes, and blood counts.

Too much tacrolimus? You risk kidney failure. Too little? Rejection looms. The goal is a narrow window - the sweet spot where your immune system is quiet, but not asleep.

Doctors adjust doses based on:

- Drug blood levels (trough levels)

- Weight changes

- Other medications you’re taking (some antibiotics or antifungals can spike your immunosuppressant levels dangerously)

- Signs of infection or rejection

Don’t start any new supplement, herb, or over-the-counter drug without checking with your transplant team. St. John’s wort can drop your tacrolimus levels by 50%. Grapefruit juice can double them. Both are dangerous.

Is There Hope for a Future Without Daily Pills?

Scientists are working on tolerance - a state where the immune system accepts the new organ without drugs. Some patients have achieved this after years of careful tapering, but it’s rare.

Early trials are testing cell therapies and regulatory T-cell infusions to retrain the immune system. But these are still experimental. For now, the pills are your shield.

What’s clear is this: transplant survival has improved dramatically. A kidney transplant recipient today lives longer than someone on dialysis. But the quality of those extra years depends on how well you manage your meds. It’s not about being perfect. It’s about being consistent. One pill, every day, for life.

Can I stop taking immunosuppressants if I feel fine?

No. Feeling fine doesn’t mean your immune system has stopped trying to reject your organ. Transplant rejection can happen without symptoms. Stopping your meds - even for a few days - can cause rapid organ failure. Always consult your transplant team before making any changes.

Do all transplant patients take the same drugs?

No. Drug choices depend on the organ transplanted, your age, kidney and liver function, risk of infection or cancer, and how your body responds to the medication. A liver transplant patient might avoid sirolimus due to higher death risk, while a kidney patient might switch to it to protect kidney function. Your regimen is personalized.

What should I do if I miss a dose?

If you miss a dose by less than 4 hours, take it as soon as you remember. If it’s been longer, skip the missed dose and take your next one at the regular time. Never double up. Call your transplant center immediately - they’ll tell you if you need extra monitoring or a blood test.

Can immunosuppressants cause weight gain?

Yes - especially corticosteroids like prednisone. They increase appetite, cause fluid retention, and change how your body stores fat. Weight gain is common in the first year. Diet and exercise help, but you may need to accept some changes. Your doctor can help you switch to steroid-free regimens if it becomes a health issue.

Are there cheaper alternatives to brand-name immunosuppressants?

Yes. Generic versions of tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and cyclosporine are available and just as effective. Many insurance plans require you to try generics first. Ask your pharmacist or transplant coordinator about switching - it can cut your monthly cost by 50-80%.

How often do I need blood tests?

In the first 3 months, you’ll likely have blood work weekly or biweekly. After that, it tapers to every 2-4 weeks for the first year, then every 1-3 months. If your doses change or you get sick, you may need more frequent testing. Never skip them - they’re your early warning system.

What Comes Next?

If you’re newly transplanted, focus on building routines. Use apps. Talk to your pharmacist. Join a support group. If you’ve been on meds for years, review your regimen with your doctor - maybe it’s time to simplify or switch to a less toxic drug.

Transplant isn’t a cure. It’s a lifelong partnership between you and your medicine. The goal isn’t to feel normal. It’s to stay alive - and to live well enough to enjoy the time you’ve been given.

Wesley Phillips

December 8, 2025 AT 03:42Kyle Oksten

December 8, 2025 AT 09:55Sam Mathew Cheriyan

December 9, 2025 AT 19:27Helen Maples

December 11, 2025 AT 14:17David Brooks

December 12, 2025 AT 17:07Nicholas Heer

December 12, 2025 AT 19:12Kyle Flores

December 14, 2025 AT 18:38Ryan Sullivan

December 16, 2025 AT 13:18Olivia Hand

December 17, 2025 AT 22:39Jane Quitain

December 19, 2025 AT 18:05Ernie Blevins

December 21, 2025 AT 17:30