Bone Health Risk Calculator

This tool estimates potential bone mineral density (BMD) changes from mefenamic acid use based on clinical research data. Remember, this is an estimate and should not replace professional medical advice.

Estimated Bone Health Impact

Recommendations:

When evaluating Mefenamic acid a non‑steroidal anti‑inflammatory drug (NSAID) commonly used for migraine and menstrual pain, many patients wonder whether it could be quietly weakening their skeleton. The short answer is that the drug can influence bone turnover, but the magnitude of the effect depends on dose, duration, and individual risk factors. This article breaks down the biology, reviews the latest research, and gives practical tips for anyone who takes or prescribes the medication.

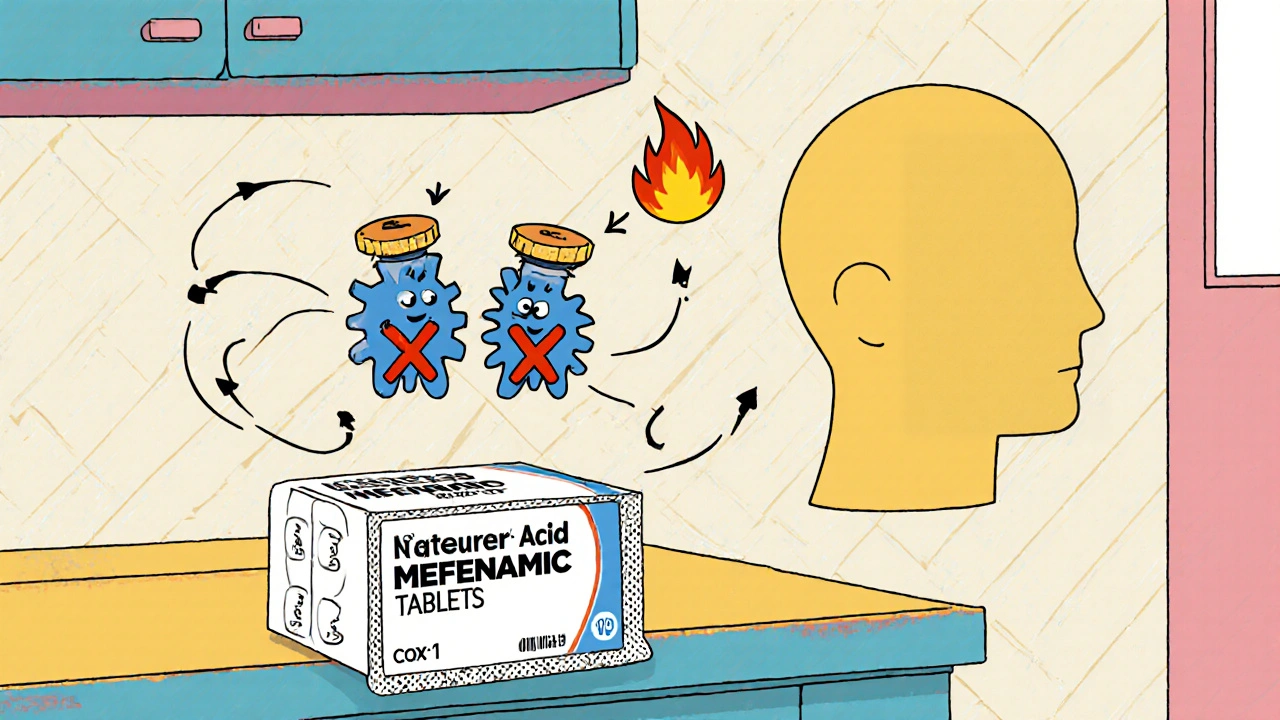

What is mefenamic acid?

Mefenamic acid belongs to the anthranilic acid class of NSAIDs. It works by inhibiting cyclo‑oxygenase (COX) enzymes, mainly COX‑1 and COX‑2, which lowers prostaglandin production and reduces inflammation and pain. Typical oral doses range from 250 mg to 500 mg every 4‑6 hours, with a maximum daily dose of 1.5 g. Because it is metabolized in the liver and excreted by the kidneys, clinicians usually avoid it in patients with severe hepatic or renal impairment.

How bone health is measured

Bone quality is most often expressed as Bone Mineral Density the amount of mineral (mainly calcium) packed into a given area of bone, measured in g/cm². Dual‑energy X‑ray absorptiometry (DXA) scans provide a T‑score that compares a person’s bone density to a healthy young adult. A T‑score of -2.5 or lower defines osteoporosis, while a score between -1.0 and -2.5 indicates osteopenia, a precursor to full‑blown bone loss.

Why NSAIDs matter for bone metabolism

Bone is a living tissue that constantly remodels through the coordinated activity of osteoclasts (which break down bone) and osteoblasts (which build new bone). Prostaglandins, especially PGE2, stimulate osteoblast function and help maintain bone formation. By blocking COX enzymes, NSAIDs reduce prostaglandin synthesis, potentially tilting the balance toward resorption. However, the effect is not uniform across all NSAIDs; selectivity for COX‑2, dosing patterns, and patient age all shape outcomes.

Clinical evidence on mefenamic acid and bone density

- Short‑term studies (≤ 6 weeks): Randomized trials in healthy volunteers showed no significant change in DXA‑derived BMD after a 4‑week course of 500 mg mefenamic acid taken twice daily. Serum markers of bone turnover (CTx for resorption, P1NP for formation) remained within normal ranges.

- Long‑term observational data: A 2019 cohort of 1,212 chronic migraine patients using mefenamic acid for ≥ 2 years reported a 1.8 % greater decline in lumbar spine BMD compared to matched controls on acetaminophen. The effect persisted after adjusting for age, BMI, calcium intake, and steroid use.

- Animal models: Rats given daily 30 mg/kg mefenamic acid for 12 weeks displayed reduced trabecular thickness and lower expression of osteogenic genes (Runx2, Osterix). However, the magnitude was less severe than with indomethacin, another NSAID with stronger COX‑2 inhibition.

Overall, the data suggest a modest, dose‑dependent impact on bone health, noticeable mainly with prolonged use and in individuals already at risk for osteoporosis.

How it compares with other NSAIDs

| NSAID | COX selectivity | Typical dose | Average BMD change (2 yrs) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mefenamic acid | Non‑selective (COX‑1 ≥ COX‑2) | 500 mg BID | -1.5 % (lumbar spine) | Effect more pronounced in post‑menopausal women |

| Ibuprofen | Non‑selective (COX‑1 ≈ COX‑2) | 400 mg TID | -0.8 % | Short‑term use shows negligible change |

| Naproxen | COX‑1 preferring | 250 mg BID | -0.5 % | Lower impact on PGE2 suppression |

| Diclofenac | COX‑2 selective | 75 mg BID | -2.2 % | Higher bone resorption markers |

The table shows that mefenamic acid sits in the middle of the pack: worse than ibuprofen or naproxen for long‑term bone health, but better than more COX‑2‑selective agents like diclofenac.

Practical implications for patients

- Assess baseline risk. Use FRAX or DXA if the patient is over 50, post‑menopausal, or has a family history of fractures.

- Limit duration. If mefenamic acid is needed for chronic conditions, aim for the lowest effective dose and re‑evaluate every 6‑12 months.

- Supplement wisely. Ensure adequate calcium (1,000-1,200 mg/day) and vitamin D (800-1,000 IU/day) to counteract any potential resorption.

- Consider alternatives. For patients with high osteoporosis risk, ibuprofen or naproxen may be safer choices, or a non‑NSAID analgesic like acetaminophen.

- Monitor. Repeat DXA after 2 years of continuous use, or sooner if the patient reports a fracture or sudden height loss.

Guidance for prescribers

- Document indication and expected treatment length in the medical record.

- Ask about other bone‑affecting drugs (glucocorticoids, PPIs, anticonvulsants).

- Educate patients on lifestyle factors: weight‑bearing exercise, smoking cessation, and limiting alcohol.

- If the patient already has osteopenia, discuss the risk‑benefit ratio and possibly choose a NSAID with lower COX‑2 affinity.

- Use electronic prescribing alerts that flag prolonged NSAID use in high‑risk groups.

Key take‑aways

- Mefenamic acid can slightly decrease bone mineral density when used long‑term, especially in older women.

- The effect is dose‑dependent and less severe than that of highly COX‑2‑selective NSAIDs.

- Regular bone health screening and adequate calcium/vitamin D can mitigate the risk.

- Consider alternative analgesics for patients with existing osteoporosis or high fracture risk.

Can a short course of mefenamic acid damage my bones?

Short courses (up to 2 weeks) have not shown any measurable impact on bone mineral density in clinical trials. The risk rises only with repeated or chronic use.

How does mefenamic acid compare to ibuprofen for bone health?

Both are non‑selective NSAIDs, but studies suggest ibuprofen leads to a slightly smaller decline in BMD over two years (about -0.8 % vs -1.5 % for mefenamic acid). The difference is modest and usually clinically irrelevant unless the patient already has low bone mass.

Should I get a DXA scan if I’m on mefenamic acid?

If you’re over 50, post‑menopausal, or have other risk factors (family history, steroids, low calcium intake), a baseline DXA is wise. Re‑scan after 2 years of continuous therapy.

Can calcium and vitamin D supplements offset the bone loss?

Adequate calcium (1,000-1,200 mg/day) and vitamin D (800-1,000 IU/day) support bone formation and can blunt the modest resorptive effect of NSAIDs, including mefenamic acid.

Is there a safer NSAID for someone with osteoporosis?

Ibuprofen or naproxen, taken at the lowest effective dose, are generally considered safer than COX‑2‑selective agents. Non‑NSAID options such as acetaminophen or topical analgesics avoid the bone‑related risk altogether.

Ericka Suarez

October 21, 2025 AT 17:33We gotta stop these pharma tricks that sneak into our bodies and *slowly* chew away teh bones of this great nation, because if our skeletons fall, so does everything we stand for.

Chirag Muthoo

October 21, 2025 AT 17:45It is important to recognize that the modest bone density reduction associated with prolonged mefenamic acid therapy can be mitigated through vigilant monitoring and appropriate supplementation, thereby ensuring patient safety without compromising analgesic efficacy.

Lolita Gaela

October 21, 2025 AT 18:10The pharmacodynamic profile of mefenamic acid reveals a non‑selective inhibition of both COX‑1 and COX‑2 isoenzymes, resulting in a measurable decrease in prostaglandin E2 synthesis.

Prostaglandin E2 functions as a pivotal anabolic mediator in osteoblastic differentiation, primarily through the EP4 receptor signaling cascade.

Consequently, chronic attenuation of PGE2 levels can shift the remodeling equilibrium toward osteoclastic resorption, as evidenced by elevated serum C‑telopeptide (CTX) concentrations.

Longitudinal cohort analyses have quantified an average lumbar spine BMD decline of approximately 1.5 % over a two‑year interval in patients adhering to a 500 mg BID regimen.

This decrement, while statistically significant, remains below the threshold commonly associated with clinical osteoporotic fractures in otherwise healthy individuals.

Nevertheless, subgroup stratification indicates that post‑menopausal females exhibit an amplified susceptibility, with reported BMD reductions approaching 2.2 % under identical exposure conditions.

The mechanistic basis for this gender disparity appears to involve estrogen‑mediated modulation of COX expression, which may potentiate NSAID‑induced osteoclastic activity.

In vitro studies utilizing primary human osteoblast cultures have demonstrated down‑regulation of osteogenic transcription factors RUNX2 and Osterix following mefenamic acid treatment at concentrations mirroring therapeutic plasma levels.

Parallel murine models corroborate these findings, displaying compromised trabecular microarchitecture and reduced mineral apposition rates after twelve weeks of daily dosing.

Importantly, comparative pharmacology reveals that agents with heightened COX‑2 selectivity, such as diclofenac, precipitate more pronounced bone turnover perturbations, as reflected by greater increases in N‑terminal telopeptide (NTX) levels.

Conversely, NSAIDs with a preferential COX‑1 inhibition profile, including naproxen, tend to exert a comparatively attenuated impact on skeletal homeostasis.

From a clinical management perspective, the incorporation of dual-energy X‑ray absorptiometry (DXA) baseline assessments is recommended for patients exceeding 50 years of age or possessing additional osteoporotic risk factors.

Subsequent bone mineral density monitoring should be scheduled at biennial intervals to detect subclinical declines and facilitate timely therapeutic adjustments.

Adjunctive calcium intake of 1,200 mg per day and vitamin D supplementation at 800–1,000 IU daily have been shown to partially offset NSAID‑related bone loss by enhancing mineralization efficiency.

Ultimately, judicious prescribing of mefenamic acid, coupled with individualized risk stratification and preventive supplementation, enables clinicians to balance analgesic benefits against potential skeletal compromise.

Giusto Madison

October 21, 2025 AT 18:20Look, the science is solid-if you’re gonna stay on mefenamic for months, pair it with calcium, vitamin D, and a weight‑bearing routine, or you’ll be asking why your hips feel like jelly.

erica fenty

October 21, 2025 AT 18:30Great summary; however, consider the pharmacokinetic half‑life, patient adherence, and potential drug‑drug interactions-especially with glucocorticoids; all factors that could modulate BMD outcomes.

Xavier Lusky

October 21, 2025 AT 18:40What they don’t tell you is that the pharmaceutical lobby quietly funds studies that downplay the bone‑weakening effects of mefenamic acid, ensuring the market stays profitable while our skeletons silently crumble.

Esther Olabisi

October 21, 2025 AT 18:50Oh sure, just sprinkle some calcium and pretend everything’s fine 😂🦴💊.

Vivian Annastasia

October 21, 2025 AT 19:00Because “sprinkling” calcium magically reverses years of microarchitectural damage-clearly, we’ve all been overthinking the entire field of osteology.

John Price

October 21, 2025 AT 19:10Bone loss from mefenamic is modest unless you’re already at risk.

eric smith

October 21, 2025 AT 19:20Obviously you missed the nuance: the cumulative effect of even a “modest” loss adds up over a decade, and that’s exactly why clinicians should heed the guidelines rather than rely on gut feeling.