How Hepatitis A Spreads Through Food

You might think of hepatitis A as something you catch from dirty water or bad hygiene-but in the U.S. and other developed countries, it’s often spread through food. Not because the food itself is rotten, but because someone who’s infected handled it without washing their hands properly. The virus, called HAV, is tiny, tough, and doesn’t need much to make you sick. As few as 10 to 100 virus particles can cause infection. That’s less than a speck of dust.

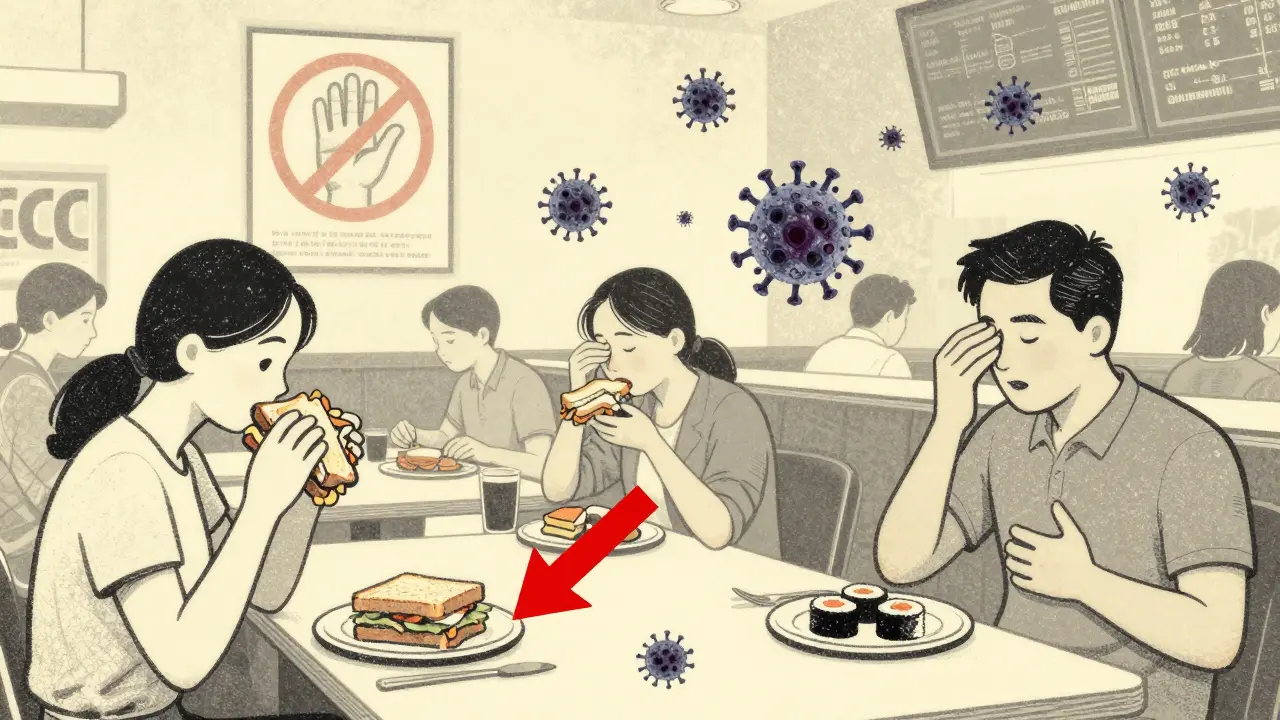

It doesn’t take much for this to happen. Imagine a food worker with hepatitis A preparing a salad. They use the bathroom, don’t wash their hands thoroughly, then pick up lettuce with bare fingers. Studies show nearly 10% of the virus on their skin can transfer to the food in just 10 seconds of light contact. That lettuce goes to a restaurant, gets served, and within weeks, a dozen customers start feeling sick. This isn’t rare. In 2023, the CDC reported that foodborne outbreaks accounted for up to 25% of all hepatitis A cases during major incidents.

Some foods are riskier than others. Shellfish, like oysters and clams, are a top concern because they’re often harvested from waters contaminated with sewage. If the water has more than 14 fecal coliforms per 100 milliliters, the FDA considers it unsafe. Yet, 92% of shellfish-related outbreaks come from exactly this source. Ready-to-eat foods-sandwiches, sushi, salads, fruit, and baked goods-are also common culprits. Why? Because they’re not cooked after handling. Heat kills the virus, but only if it’s applied properly. HAV can survive at 60°C for an hour, and it takes 85°C for a full minute to destroy it. Many people think “warm enough” is safe, but it’s not.

The virus is also shockingly durable. It can live on stainless steel surfaces for up to 30 days. In dried form, it stays infectious for four weeks. Freeze it? It survives for years. That’s why outbreaks can pop up weeks after the initial contamination. You might eat something on Monday and not feel sick until the end of the month. By then, you’ve been around family, coworkers, and public spaces-spreading it without knowing.

Who’s Most at Risk-and Why It’s Hard to Stop

One of the biggest problems with hepatitis A is that most people don’t know they’re sick until it’s too late. About 30 to 50% of infected adults show no symptoms at all. In kids under six, it’s even higher-up to 90% show no signs. That means someone can be shedding the virus in their stool, contaminating food, and spreading it to others for weeks before anyone realizes there’s a problem.

Food handlers are at the center of this. They’re not careless-they’re often tired, overworked, underpaid, and unaware. Surveys show only 35% of food workers can correctly name hepatitis A symptoms. Just 28% know that post-exposure treatment must happen within 14 days. And even fewer understand that you can be contagious before you even feel sick.

Turnover in the food industry makes this worse. In quick-service restaurants, staff turnover averages 150% per year. That means new people are constantly joining without training. Language barriers affect 45% of kitchen staff in big cities. Many don’t understand safety instructions written in English. Restroom access is another issue: 22% of inspected food establishments don’t have enough handwashing stations. One station for every 15 employees? That’s the standard. Most don’t meet it.

And vaccination rates? Shockingly low. Even though the CDC recommends hepatitis A vaccine for all food workers, fewer than 30% of them are vaccinated. In seasonal jobs-like summer food stands or holiday pop-ups-it drops to 7%. That’s not because people are against vaccines. It’s because they don’t know they need one, or they can’t afford it, or they’re told it’s “not required.”

What to Do After You’ve Been Exposed

If you’ve eaten food from a place where someone later tested positive for hepatitis A, or if you’re a food worker who touched something contaminated, time matters. You have 14 days to act. After that, post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) won’t help.

There are two options for PEP:

- Hepatitis A vaccine-a single shot for people aged 1 to 40. It’s cheap, effective, and gives protection for at least 25 years. It works by teaching your body to fight the virus before it takes hold.

- Immune globulin (IG)-a shot of antibodies that gives immediate, short-term protection. It lasts only 2 to 5 months. It’s used for people over 40, pregnant women, or those with liver disease who can’t get the vaccine.

The vaccine costs $50 to $75. IG costs $150 to $300. But the real cost comes later. A single outbreak investigation can run $100,000 to $500,000. That’s why getting the vaccine right away saves money, lives, and stress.

Here’s the catch: PEP doesn’t stop you from spreading the virus right away. Even if you get the shot, you still need to avoid handling food for six weeks. Wash your hands after every bathroom break. Don’t touch ready-to-eat food barehanded. If you’re a food worker, stay home. You’re still contagious, even if you feel fine.

And don’t assume you’re safe just because you got the shot. The vaccine takes about two weeks to build full immunity. That’s why the CDC says: PEP + hand hygiene = your best defense.

How Food Businesses Can Prevent Outbreaks

Restaurants, cafeterias, and food trucks can stop hepatitis A before it starts. But most aren’t doing enough.

Here’s what works:

- Use gloves or utensils for all ready-to-eat food. Bare-hand contact is the #1 cause of transmission. Washington State found that 78% of food places still let workers touch food with bare hands.

- Train with hands-on practice. Reading a manual doesn’t work. Watching someone show you how to wash your hands properly, then doing it yourself, improves compliance by 65%.

- Test wastewater. Pilot programs in some states now check restaurant drains for hepatitis A virus. It’s not perfect yet, but it can catch asymptomatic carriers before anyone gets sick.

- Require vaccination. As of January 2024, 14 U.S. states now require hepatitis A vaccine for food handlers. California’s law, passed in 2022, prevented 120 infections and saved $1.2 million in outbreak costs. That’s a return of $3.20 for every $1 spent on vaccination.

Some places are trying financial incentives. Offering a $50 bonus for getting vaccinated raised rates by 38 percentage points. That’s huge. And it’s cheaper than closing a restaurant for a week because of an outbreak.

But the biggest barrier? Culture. Many owners think, “We’re clean. We don’t need this.” But cleanliness isn’t enough. The virus is too tough. You need vaccines, gloves, training, and rules-working together.

What You Can Do Right Now

You don’t need to be a health official to protect yourself and others. Here’s what you can do today:

- If you’re a food worker and you haven’t been vaccinated, get the shot. Talk to your manager. Ask if your employer offers it for free.

- If you’re a customer and you hear about a hepatitis A exposure at a restaurant, check if you ate there in the last 14 days. If yes, call your doctor or local health department. Don’t wait.

- Wash your hands with soap and water for 20 seconds after using the bathroom and before eating. That’s longer than singing “Happy Birthday” twice. Water alone cuts risk by only 30%. Soap and scrubbing? 70%.

- If you’re traveling to a country where hepatitis A is common, get vaccinated before you go-even if you’re just going for a week.

There’s no magic fix. But you don’t need one. You just need to act before it’s too late.

How Hepatitis A Is Diagnosed and Managed

Doctors don’t diagnose hepatitis A by symptoms alone. Many other illnesses-flu, stomach bugs, even food poisoning-look the same. The only way to confirm it is through blood tests.

The key test looks for HAV IgM antibodies. These show up 5 to 10 days before symptoms start and stay in your blood for 3 to 6 months. If they’re present, you have a recent infection. Another test looks for HAV RNA in your blood or stool. That’s used in outbreaks to track how the virus is spreading.

There’s no cure for hepatitis A. Your body clears it on its own. Treatment is about rest, fluids, and avoiding alcohol and medications that stress the liver. Most people recover fully within a few weeks. But for some-especially those over 50 or with existing liver disease-it can be serious. In rare cases, it leads to liver failure.

That’s why prevention matters more than treatment. Once someone is infected, the risk of spreading it to others is high. That’s why food workers must stay home for at least 7 days after jaundice appears-or two weeks after symptoms start, depending on local rules. California requires 14 days. Iowa says 7 days after jaundice. Rules vary, but the goal is the same: stop the spread.